Beyond Water: A Full Life Cycle Look at Fabric Sustainability

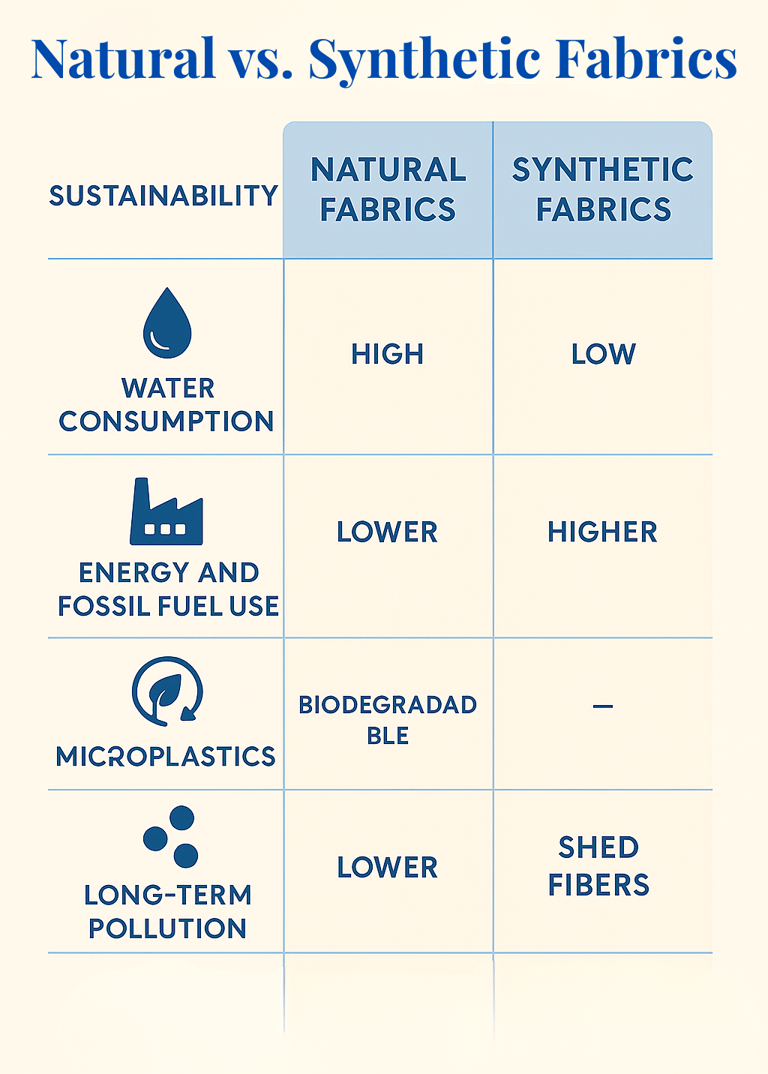

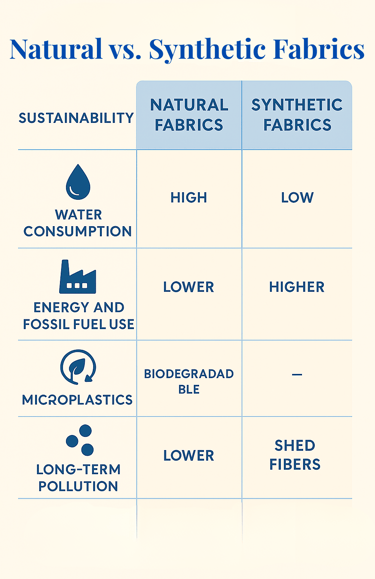

Natural vs Synthetic Fabrics: Which Is Truly More Sustainable? This post will compare the sustainability of natural vs synthetic fabrics considering the full life cycle of the fabric, water consumption, energy & fossil fuel use, biodegradability, and other long term effects.

9/26/20255 min read

When most people think about fabric sustainability, one statistic inevitably comes up: cotton uses an astonishing amount of water. Stories about “the 2,700 liters it takes to make one cotton T-shirt” circulate widely on social media, often followed by arguments that synthetic fabrics like polyester are inherently better for the planet. But sustainability is more nuanced than a single metric. Looking only at water use risks ignoring other major impacts, from carbon emissions to microplastic pollution, and even how long a garment lasts before it heads to a landfill.

A more holistic way to measure fabric impact is to look at its life cycle—from raw material extraction to production, use, and end-of-life. When we take the full journey of a fabric into account, the sustainability story gets far more complex—and much more interesting.

Why Water Isn’t the Whole Story

The water footprint of cotton is real. Conventional cotton farming, especially in arid regions, relies on irrigation, contributing to depleted aquifers and stressed ecosystems. Some infamous examples, like the drying of the Aral Sea due to irrigation for cotton fields, have made water use a flashpoint in sustainable fashion discussions.

By comparison, polyester, nylon, and other synthetic fabrics are not grown in fields and don’t need irrigation at all, which makes their direct water consumption much lower. From a water perspective alone, synthetics seem like an environmental win. But if we stop there, we miss the larger picture.

Life Cycle Assessments: The Bigger Picture

A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a tool researchers use to evaluate the total environmental impact of a product, from raw material extraction (“cradle”) to disposal or recycling (“grave”). For fabrics, LCAs consider:

Water consumption (for fiber growth, dyeing, finishing, and washing during use)

Energy and fossil fuel use (for synthetic fiber production and textile manufacturing)

Greenhouse gas emissions (from energy, chemical processing, and livestock in the case of wool or silk)

Toxic chemical impacts (pesticides, dye effluents, finishing treatments)

End-of-life behavior (biodegradability, recyclability, landfill impact)

When you look at an entire life cycle, some assumptions about “sustainable” fabrics start to unravel.

Natural Fabrics: Biodegradable but Resource Intensive

Cotton, linen, hemp, wool, and silk are natural fibers, meaning they come from plants or animals rather than fossil fuels. Their biggest environmental impacts often come at the beginning of their life cycle: farming.

Cotton uses significant water when grown in irrigated regions and often relies on pesticides unless it’s organic.

Wool production generates methane emissions from sheep and can lead to land degradation if overgrazed.

Silk is labor- and energy-intensive because it requires heating and handling of delicate cocoons.

However, natural fibers have major advantages at the end of life. When untreated and undyed, cotton, linen, hemp, and wool can biodegrade in compost conditions, breaking down into natural materials rather than persisting for centuries in landfills. They also shed natural fibers (like cellulose or protein), which biodegrade more easily in water than synthetics.

Synthetic Fabrics: Low Water, High Carbon

Polyester, nylon, acrylic, and spandex are petrochemical-based fibers derived from crude oil or natural gas. Their production requires no farmland or irrigation, which is why their water footprint is often lower than that of cotton or silk.

But there’s a catch: synthetics are extremely energy-intensive to produce. Converting fossil fuels into polymer fibers requires high heat and industrial processing, resulting in a high carbon footprint—in many cases double or triple that of cotton.

Synthetics also create long-term pollution problems:

Microplastics: Every time synthetic fabrics are washed, tiny fibers shed and enter waterways. These microplastics don’t biodegrade and accumulate in oceans and even inside animals (and humans).

Persistence in landfills: A polyester T-shirt could take hundreds of years to break down, and even then, it breaks into smaller plastic fragments, not harmless natural matter.

How Consumers Can Make Better Choices

Read Labels Carefully

Look for information about fiber content and consider how long you’ll realistically wear the item. A 100% polyester dress worn 30 times may be better than a trendy cotton top worn twice.Seek Certifications

For natural fibers, look for standards like GOTS (Global Organic Textile Standard) or OEKO-TEX, which indicate reduced pesticide use and safer dyeing processes. For synthetics, recycled polyester (often called rPET) has a significantly lower footprint than virgin polyester.Wash Smart

Use cold water, wash less frequently, and use filters or washing bags (like Guppyfriend) to reduce microfiber pollution from synthetics.Invest in Longevity

Choose timeless styles and higher-quality fabrics, so garments last longer. The fewer items you buy and discard, the lower your overall fashion footprint.End-of-Life Planning

Donate, resell, or repurpose clothes instead of tossing them in the trash. If possible, compost natural fabrics that are untreated and undyed.

Sustainability isn’t about one magic fiber. It’s about understanding trade-offs and making intentional choices. Cotton may drink up more water than polyester, but polyester lingers for centuries. Linen may take less water than cotton but wrinkles easily and costs more. Recycled polyester reduces waste but still sheds microplastics.

The next time you pick up a shirt, consider its entire journey—from the field or refinery to your closet and beyond. True sustainability is about slowing down, buying less, and valuing every piece of clothing for the resources and effort it represents.

End-of-Life: The Waste Crisis

When garments reach the end of their useful life, natural fibers again have an advantage: they’re inherently biodegradable. Cotton, hemp, and linen will eventually break down, especially if composted or left untreated. Wool and silk biodegrade as well, though more slowly.

Synthetics, on the other hand, persist. Recycling options exist for polyester and nylon, but the infrastructure is limited, and blended fabrics (like cotton-poly mixes) are notoriously difficult to separate and process. Most synthetics end up in landfills or incinerators, where they either contribute to microplastic pollution or release carbon dioxide and toxic fumes when burned.

So, Which Is More Sustainable?

If you look at only water, synthetic fabrics seem to win. If you look at carbon emissions and long-term pollution, natural fabrics—especially linen, hemp, and organic cotton—often have the edge. But the reality is that no fabric is perfectly sustainable. The best choice often depends on the context:

For durability and athletic wear: recycled polyester or nylon may make sense, especially when designed for long-term use.

For everyday basics: natural fibers like organic cotton, linen, and hemp can be better for biodegradability and comfort.

For reducing waste: choosing high-quality, long-lasting garments—regardless of fabric—is often more impactful than the fiber itself.